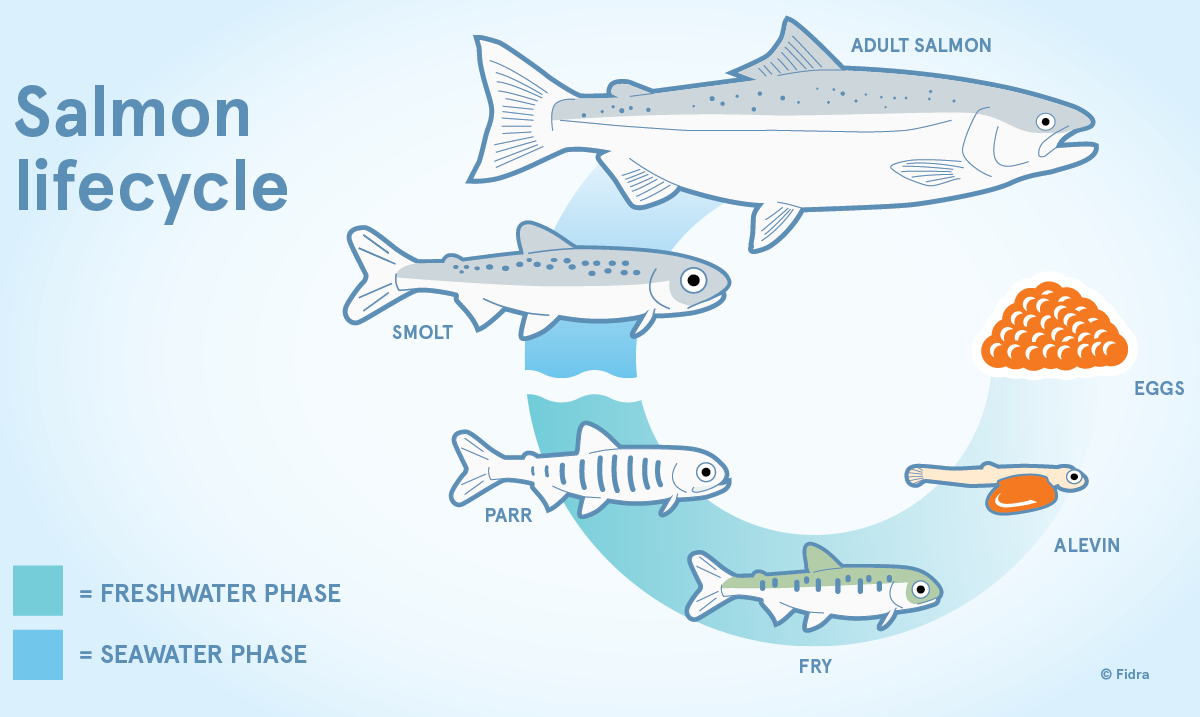

The Life Cycle of a Salmon

Egg

The female salmon lay fertilized eggs in the redds they dug out. The eggs will hatch in about 3 months.

Alevin

Once the salmon hatch from the eggs, they are called alevins. During this stage, alevins will feed on a yolk sac attached to their bellies and stay hidden in gravel.

Fry

Alevins will become fries once they have fully consumed their yolk sac. During this phase, they will stay in freshwater rivers to feed on small aquatic insects.

Parr

During this stage, the fries will start to develop vertical markings along their side.

Smolt

The salmon entering saltwater are called smolts. They migrate from the rivers to the sea. Most species will remain in estuaries to adapt to the transition, though the time varies amongst different species.

Adult Salmon

Salmons spend around one to eight years feeding and maturing in the ocean.

Spawning Salmon

When it is time for salmon to spawn again, they migrate back to their natal streams to spawn, where they go through changes such as shape and colour.

They will not feed in freshwater as their only instinct is to make it to the spawning grounds.

Salmon will die after spawning.